In September of 2017 the amazing book TAPA was launched in Paris. I was privileged to be one of the book’s many authors, and asked to write about the bark cloth on my former home island of Atiu (left). I was also invited to exhibit some of my works for the occasion (below a detail of my tapa-lace panel with Marquesan dance costumes in the background).

In September of 2017 the amazing book TAPA was launched in Paris. I was privileged to be one of the book’s many authors, and asked to write about the bark cloth on my former home island of Atiu (left). I was also invited to exhibit some of my works for the occasion (below a detail of my tapa-lace panel with Marquesan dance costumes in the background).

During the exhibition I met French artist and art restorer Marion Dumaine. Marion exhibited lengths of Tongan tapa beautifully decorated with natural pigments and gold leaf. Being both interested in barkcloth, the idea arose to meet in August 2018 and hold an experimental workshop. My German girlfriend Christel Weingart, felt artist, painter and published author, who had used barkcloth in a sculptural way many years ago, would also join us. Raymond and Colette Cristini offered us free of charge their lovely summer house in Tarascon sur Ariège (France) for our experiments.

During the exhibition I met French artist and art restorer Marion Dumaine. Marion exhibited lengths of Tongan tapa beautifully decorated with natural pigments and gold leaf. Being both interested in barkcloth, the idea arose to meet in August 2018 and hold an experimental workshop. My German girlfriend Christel Weingart, felt artist, painter and published author, who had used barkcloth in a sculptural way many years ago, would also join us. Raymond and Colette Cristini offered us free of charge their lovely summer house in Tarascon sur Ariège (France) for our experiments.  Our first interest was to check if there were any suitable plants growing in Europe whose inner bark could be successfully beaten into usable sheets. Marion’s cousin had had to cut down a fig tree, ficus carica, one of the many fig species and thus distantly related to the plant family from which tapa is being made in the South Pacific islands and other areas. They had kept some branches for us to explore.

Our first interest was to check if there were any suitable plants growing in Europe whose inner bark could be successfully beaten into usable sheets. Marion’s cousin had had to cut down a fig tree, ficus carica, one of the many fig species and thus distantly related to the plant family from which tapa is being made in the South Pacific islands and other areas. They had kept some branches for us to explore.

We boiled these in water for three hours (left: Christel checking on the branches) and spent an entire day shaving off the outer bark. The bast could be removed and smelled, felt and looked just like that of the Banyan roots I had worked with in the Cook Islands. We fermented it for a day, as I had done on Atiu, to make beating of the rather coarse bark easier.

We boiled these in water for three hours (left: Christel checking on the branches) and spent an entire day shaving off the outer bark. The bast could be removed and smelled, felt and looked just like that of the Banyan roots I had worked with in the Cook Islands. We fermented it for a day, as I had done on Atiu, to make beating of the rather coarse bark easier.

However when beating it, it did not stay in one piece, but dissolved into bundles of tangled fibres. So we learned our first lesson: not all fig bast is suitable for tapa making.

Marion brought some Philodendron roots from her giant plant at home to try out. It was a fiddly enterprise to shave off the outer bark. The best way of removing the inner wooden core was to just beat the root flat. When fresh, it had beautiful rusty and pink colours, however these dried into beige and brown once dry.

I took some blueprinted tapa with me which I wanted to felt into a freshly beaten length of tapa. Colette, our hostess, had brought us bundles of dried Broussonetia papyrifera (Paper Mulberry) bark from her home island of Futuna. We were grateful that Michel Charleux, the editor of the TAPA book, let us have the Marquesan-style anvil which had served for tapa demonstrations during the Paris book launch exhibition. Once the bast was beaten thin, I removed some slivers from the cyan-dyed tapa pieces and beat them into the white tapa. It worked wonderfully.

I took some blueprinted tapa with me which I wanted to felt into a freshly beaten length of tapa. Colette, our hostess, had brought us bundles of dried Broussonetia papyrifera (Paper Mulberry) bark from her home island of Futuna. We were grateful that Michel Charleux, the editor of the TAPA book, let us have the Marquesan-style anvil which had served for tapa demonstrations during the Paris book launch exhibition. Once the bast was beaten thin, I removed some slivers from the cyan-dyed tapa pieces and beat them into the white tapa. It worked wonderfully.

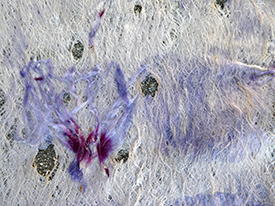

Encouraged by Marion’s experiments with the Philodendron roots, I decided to experiment with mauve coloured Rose of Sharon petals. The delicate upper parts were easy to felt into the bast, the thicker maroon centers not so well. However in the end, most of the petals had merged with the bark.

We decided to beat all strips of bark which we had already soaked in water. Both Marion and I were interested in achieving a lacy effect (left) for use in future artworks .

We decided to beat all strips of bark which we had already soaked in water. Both Marion and I were interested in achieving a lacy effect (left) for use in future artworks .

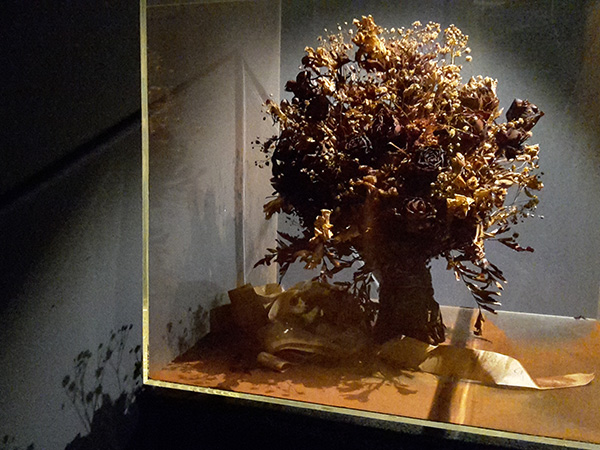

Meanwhile Christel had been using pieces of tapa to fashion some delightful three dimensional artifacts. I had seen Christel’s tapa bowls when I first met her in 2003 and had been keen to learn from her how to make them.

Over a ceramic bowl, with the help of cling film, water and cellulose glue she formed delicate vessels (left), decorated with spirals and some of the fig bast fibres from our previous experiment (right). They were especially impressive when seen in their delicate beauty against the light and blue sky of Tarascon’s summer. This was my chance and now I knew what I wanted to do with the cyan-dyed tapa pieces.

This was my chance and now I knew what I wanted to do with the cyan-dyed tapa pieces.

The blue and white patterns reminded of Delftware. After the first bowl I became more adventurous. I discovered that the pieces were double-layered and that using both layers made the bowl too opaque for what I wanted to achieve. I also used the inner, plain layer and adorned it with the remnants of the previous bowl.

Now, back in Terrassa, the three bowls I made in this enjoyable experimental workshop adorn my book shelf. They may become part of an exhibition I am hoping to have some day…